Acupuncture, Thoracic Anatomy, and Pneumothorax

A Clinical Anatomy–Based Approach to Patient Safety

Patient safety is a fundamental responsibility across all regulated acupuncture and manual therapy professions. While acupuncture is widely recognized as a safe intervention when performed appropriately, rare but serious adverse events—such as pneumothorax—underscore the importance of anatomical knowledge and sound clinical judgment.

This article focuses on thoracic cage anatomy and how a strong understanding of three-dimensional anatomical relationships plays a critical role in minimizing risk during acupuncture treatments involving the thorax.

This is not about discouraging thoracic needling.

It is about practicing within anatomical competence.

Pneumothorax in Clinical Context

A pneumothorax occurs when air enters the pleural space, potentially resulting in partial or complete lung collapse. In acupuncture practice, this may occur if a needle penetrates beyond the musculoskeletal tissues and compromises the pleura.

Large-scale studies indicate that pneumothorax associated with acupuncture is rare, particularly when compared to the overall number of treatments performed worldwide. However, it remains the most commonly reported serious adverse event related to acupuncture.

Reported incidence ranges from approximately 0.001% to 0.01% per treatment

Most cases are associated with thoracic, upper back, parascapular, and supraclavicular regions

Published analyses consistently identify anatomical misjudgment as a contributing factor

(MacPherson et al., 2001; White et al., 2004; Ernst & Zhang, 2011)

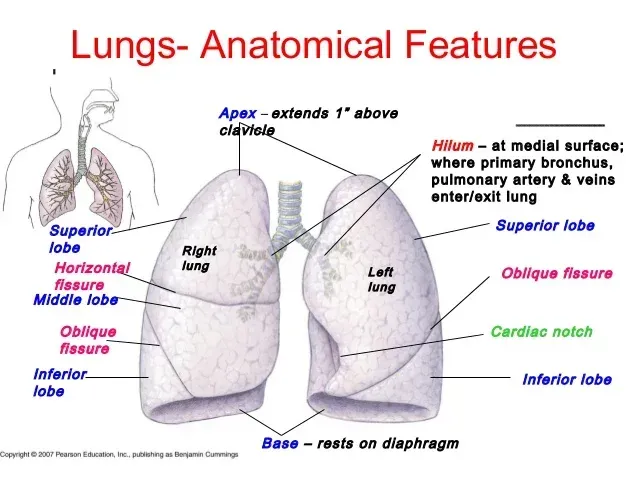

The Thoracic Cage: A Three-Dimensional Structure

A key contributor to procedural risk is oversimplification of thoracic anatomy.

The thoracic cage is not a flat or uniform structure. It is a complex, three-dimensional system composed of:

Twelve pairs of ribs with variable curvature and angulation

Intercostal spaces that change with posture and respiration

A sternum with regional depth variation

Scapulae that dynamically reposition based on arm position and muscular tone

These structures directly influence the depth, angle, and trajectory of safe needle insertion.

Understanding anatomy in three dimensions—rather than relying solely on surface landmarks—is essential for safe clinical decision-making.

Lung Borders and Rib Relationships

From an anatomical standpoint, several factors are clinically relevant:

The lung apices extend superior to the clavicles

Lung tissue lies beneath intercostal spaces, not ribs

Rib orientation becomes increasingly oblique from superior to inferior thoracic levels

Pleural reflections closely follow rib curvature

Imaging and cadaveric studies demonstrate that, in certain individuals, the distance between skin surface and pleura may be relatively small—particularly in patients with lower body mass or increased thoracic mobility.

(Gray’s Anatomy; Moore et al., Clinically Oriented Anatomy)

Common Thoracic Risk Zones

The following regions warrant increased anatomical awareness and conservative clinical judgment:

Upper Trapezius and Supraclavicular Region

Proximity to lung apices

Increased risk with inferior or medial angulation

Parascapular Region

Variable scapular positioning alters underlying anatomy

Intercostal exposure increases with scapular protraction

Thoracic Paraspinal Region

Rib angle determines whether needle trajectory moves toward or away from pleural structures

Safe parameters vary significantly by vertebral level

Individual Patient Considerations

Regulatory standards emphasize patient-specific assessment. Factors that may influence risk include:

Body composition

Thoracic posture and movement patterns

Rib cage mobility

History of thoracic surgery or trauma

A standardized approach without individual assessment increases procedural risk.

Technique, Training, and Clinical Judgment

While technique guidelines and depth recommendations may be useful as general references, they cannot replace anatomical understanding. There is no universally “safe depth” applicable to all patients or all thoracic regions.

Regulatory safety is best supported by:

Ongoing anatomical education

Clear understanding of internal structures

Conservative needle angulation in higher-risk zones

Informed consent and appropriate patient monitoring

Evidence and Professional Responsibility

Large observational studies involving hundreds of thousands of treatments continue to demonstrate that acupuncture is a low-risk intervention when performed by appropriately trained practitioners.

Importantly, reviews of adverse events suggest that experience alone does not eliminate risk—ongoing education and anatomical competence are essential throughout a practitioner’s career.

(MacPherson et al., BMJ, 2001; Ernst & Zhang, 2011)

Conclusion

Thoracic acupuncture can be performed safely within regulated practice when grounded in sound anatomical knowledge and patient-specific assessment.

A three-dimensional understanding of the thoracic cage:

Supports informed clinical decision-making

Reduces preventable complications

Enhances practitioner confidence

Aligns with regulatory expectations for safe care

As I often remind my students—knowledge is value.

In clinical practice, it is also safety.

References

MacPherson H et al. BMJ, 2001

White A et al. BMJ, 2004

Ernst E, Zhang J. American Journal of Medicine, 2011

Moore KL et al. Clinically Oriented Anatomy

Gray’s Anatomy, 41st Edition